My wife approached me today and said “I’m currently embroidering gravel. Beige, grey, boredom.” (We are both into needlework and she is making a picture of a house.)

Naturally I made a connection to working in IT. Why embroider gravel, when you can embroider unicorns? Why not become a designer and make awesome unicorns all day?

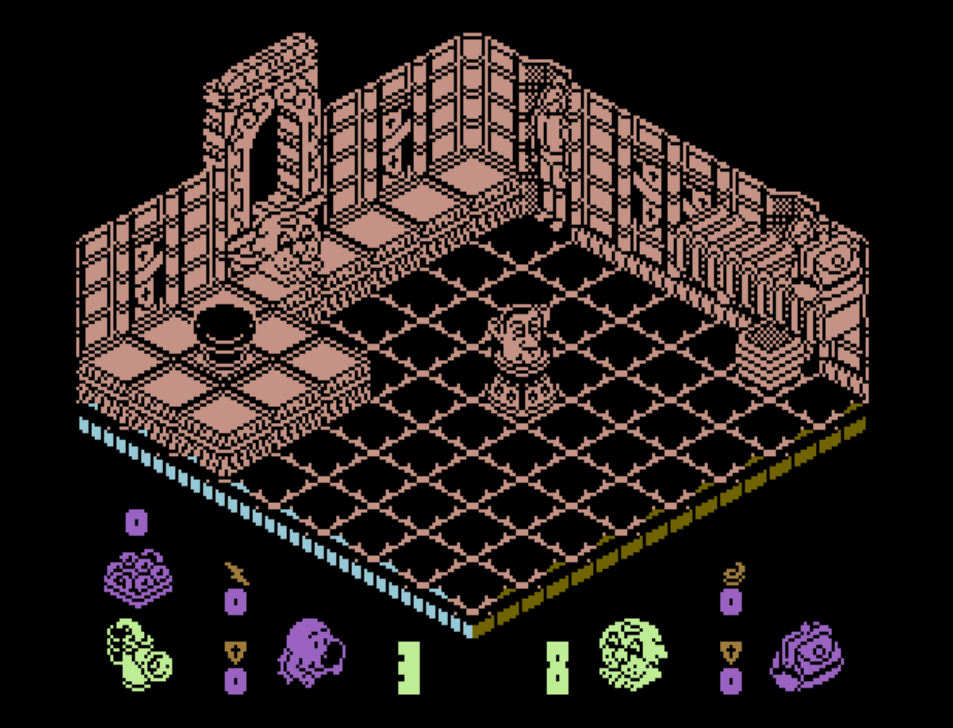

[image found via staybuckedup on Imgur]

Design is not always shiny

This was my image of a design career a few years ago when I started to embark on a path towards it.

I’ve recently been doing some career soul searching, prompted by being turned down for a design job in the past few months. (For the record, I’m definitely entirely completely over this. I just needed more experience).

Design originally attracted me with the sparkly idea of ‘making websites look and feel nice’ until I realised you actually had to talk to the people who use the software you build. Don’t get me wrong, I love hearing what users have to say about a thing you’re making. But as an introvert, the idea of all this talking made me feel a bit uneasy. It made me question: is there a place in design for introverts?

Why research?

Our team helps people in England register to do things with waste, to help manage the environmental impact. After we recently released some code, our application’s approval rating leapt up from 84% to 94%. That’s pretty amazing, seeing as many people don’t have a lot of love for government bodies or filling in forms.

I like to think that much of this is because our fantastic researcher helped us listen to our users before we made the thing.

Even now I still come across so much software that has seemingly not been researched or designed, and it amazes me that such software companies make so much money. I shudder on the inside when I hear the word “enterprise” used anywhere near software, as it is generally bad, or at best, clunky.

Solitary working

I work in Quality Assurance (QA). My part in our service was through quiet analysis of the design and code, testing it all before and after development. You do need to talk to the team to understand how it’s going to work. But a lot of QA work is solitary, and that suits me right up. Writing code to automatically test something at the push of a button can be sometimes tedious, but you learn as you go along and it’s so satisfying when it works.

I work with the best team anyone could wish for. If the team was just introverted developers and testers building stuff to some mysterious specification, we’d still get stuff done. But it would be pants. Because we didn’t talk to the end users.

Yet there is still a place for introverts in an agile team. We need the time to stop, think, analyse, question. The QA person is often the one person being cynical when the rest of the team is being enthusiastic, but this helps get any badness of the way before a product gets to users.

We are all designers in our own way.

In an article I keep going back to, Hunter S Thompson said: The goal is absolutely secondary: it is the FUNCTIONING TOWARD the goal which is important.

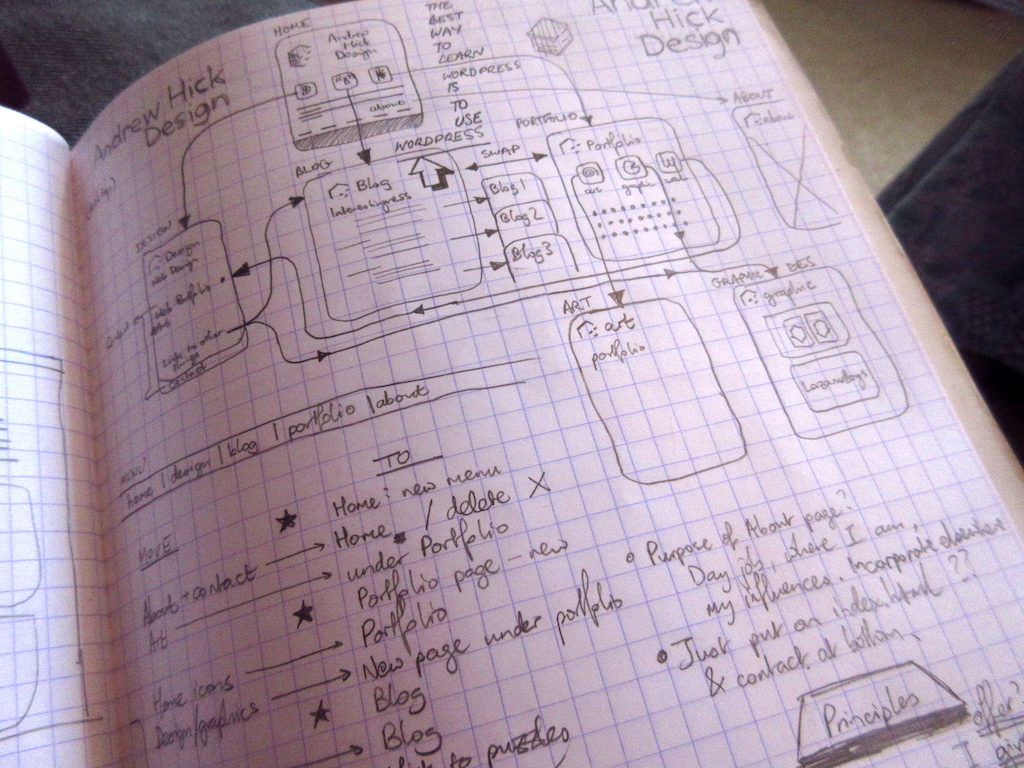

The goal of design is a noble one: to give people something they actually need. But it’s the route to the good design which is important. There are so many ways to contribute to this, whether it’s prototyping a web page, listening to an unexpected rant from a user, coding some automated tests to make sure your changes haven’t broken anything, or rewriting swathes of code to make it more efficient. To many people, the solitary coding bits might feel like embroidering gravel. But to an introvert, that can be quite enticing.

It’s not just about unicorns.

The word ‘design’ comes with an allure of hipsters with shiny Macs building pixel-perfect, razor-sharp websites, but there’s so much more to it, some glamorous, some not.

Embroidering gravel might not be sexy, but it is necessary. To an introvert, it can be as perversely enjoyable as the shiny Mac stuff. And writing elegant, efficient code is just as important to the final ‘design’.

Oh and for the record, introverts can design well, whichever discipline they ultimately end up in. Don’t worry if you don’t like talking, you just have to be able to listen.

Related: 24 ways to look like an awesome UX designer by Guy Ligertwood